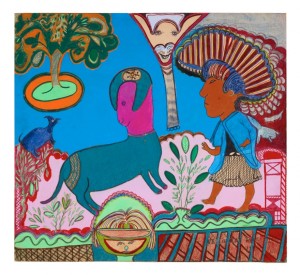

Nellie Mae Rowe, “Woman Scolding her Companion†(1981), pastel, colored pencil, crayon, and marker on paper (all images courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014)

I got to a certain age in life and without any say so on my part, I realized I was getting old. It started when the parents of the people around me started dying. The feeling accelerated when those people, the people not once or twice removed from me, but the people that made up my life, they started dying.

The summer I turned forty, my dear friend Terri-Lynn died. A few weeks later, my childhood friend Elizabeth died. A few months after that, Lisa died. And a few weeks later, Kathy died. Cancer killed all of them, none of them older than their early 50’s, all of them mothers.

Terri-Lynn was one of the best people I ever knew. We met on the internet, in a time when that was still an odd thing to say out loud. From the time we first became acquainted until she died, nine years later, we never went more than a few days without talking. She flew to see me after I had a series of heart attacks. I was too broke to visit her when she got sick.

Terri-Lynn was ten years older than me but had her child later, so her boy was years younger than my daughter. She would ask me for parenting advice. Terri-Lynn helped me appreciate Pat Conroy and turned me onto a magazine called The Oxford American.

We both were vastly more intelligent than our upbringing or educations would show. We both had opinions on, well, everything but especially on things like the best mayonnaise (Duke’s) and canned vs. poached chicken in chicken salad (poached). We both had bad luck in our taste in men.

We were both talented writers. And because of who we were and the expectations we grew up with, the only people who knew of our talent were the small band of other women we hung out with on the internet. Terri-Lynn should have been appearing on writers’ panels alongside her idols Lee Smith and Bobbi Ann Mason. She should have been giving readings and going to banquets to receive awards. But she wasn’t.

She spent a lot of time frustrated. And unhappy. Life had not turned out the way she thought it was supposed to, the way she had planned, the way our culture told her it would. There was a lot of disappointment.

Her passing left me bereft. It was the beginning of a long summer of bereavement. Terri-Lynn died. Elizabeth died. A close friend ghosted. Another close friend moved away. My daughter was having a difficult time, moved out, something we have still never discussed. It was bad.

I was paralyzed with grief. I was alone. I was living on a jagged edge.

I stayed there for a long while. Finally, I decided I was either going to have to kill myself or I was going to have to get better because the status quo was no longer endurable. I decided to get better.

It took a bit of time. These things always do. I decided I was going to learn to be content. Not happy but content. Content is an entirely different species from happy. I did a lot of work. I ate better. I read good books. I wrote. And it happened, I got content. I got okay.

And then, I felt the lump in my breast. I missed Terri-Lynn so much that summer, the summer I was diagnosed with cancer. I missed her so goddamned much. I spent a lot of time apologizing to her, for not being a better friend, for spending so much time a depressed heap of skin, for not starting the writing sooner, for giving up too soon.

I promised her, if I get out of this, if I make it, I’m going to write. I won’t waste it. I won’t let myself be yet another smart Southern redneck woman with unrealized potential. And Terri-Lynn told me to go do my thing, baby girl. She called me baby girl. Or sweet pea. But mostly, baby girl. I called her sugar pie.

I am reminded of her, all the time. She has been dead almost seven years and I still hear her voice. I meet bits of her in my day. Her memories no longer bring automatic tears but laughter. There she is, in the soundtrack to Dr. Zhivago spied in a GoodWill bin, or in the mess of beans simmering on my stove.

I am a writer. It’s what I do. I know that now. My worst day writing is better than my best day selling real estate or negotiating deals. That doesn’t mean it is easy. Doesn’t mean it doesn’t cost me something, every day. It means I am glad to pay the price. I write because it is what I am. I write because I have to. I write for Terri-Lynn and every other woman that went to her grave with the words buried inside her.

I wish you could be here to see this, Terri-Lynn. I miss you, sugar pie.